Source: The Financial Times

In 2012, just before taking over as China’s leader, Xi Jinping spent a week in the U.S in an effort to charm the American public. He visited a farm in Iowa where he had stayed as a young man and took in a Lakers basketball match in Los Angeles, posing for photographs with Magic Johnson.

His host for the trip was vice-president Joe Biden, who praised Mr. Xi for his willingness to shake up the impression Americans might have about Chinese politicians.

“This is a guy who wants to feel it and taste it, and he’s prepared to show another side of the Chinese leadership,” Mr. Biden said at the time.

Eight years later, the now Democratic presidential candidate has a very different tone. “This is a guy who doesn’t have a democratic — with a small d — bone in his body,” he said in February about Mr. Xi. “This is a guy who is a thug.”

Mr. Biden is not alone in seeing Beijing through different eyes. In the hyper-partisan Washington during the presidency of Donald Trump, Democrats and Republicans are locked in combat over the Supreme Court, the economic response to the coronavirus pandemic and even over mask wearing. China is almost the sole exception where common ground is to be found.

Joe Biden and Xi Jinping display shirts given to them by students at the International Studies Learning Center in Southgate, outside LA, in February 2012 © Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Source: The Financial Times

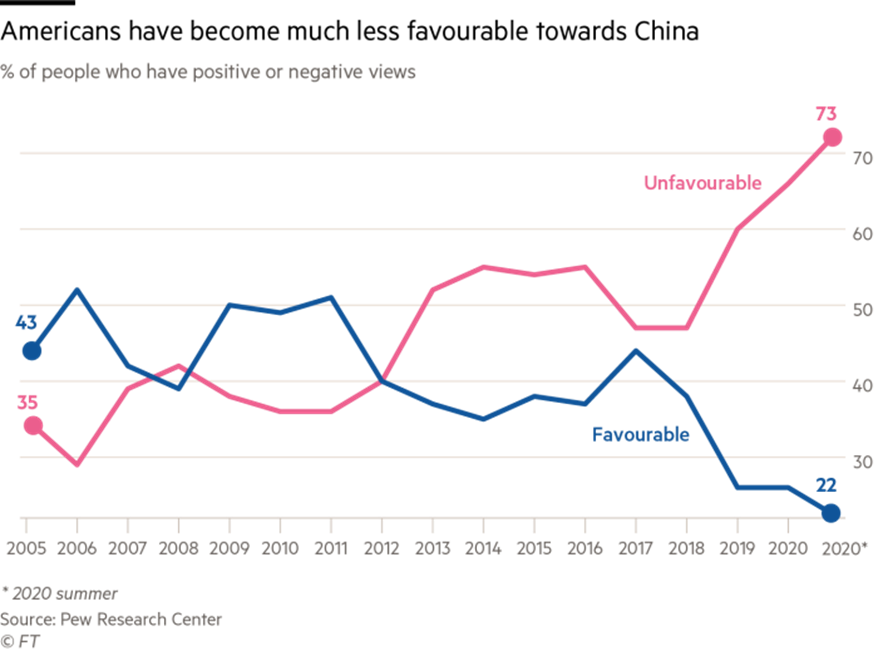

Over the past few years there has been a fundamental shift in how the U.S thinks about China that spans the political spectrum, even if some of the recent rhetoric is partly a product of both parties not wanting to appear soft before the election.

The geopolitical tensions between the U.S and China have been rising since the financial crisis more than a decade ago. China’s military started to boost its presence in the South China Sea as Beijing sought to challenge the primacy of the US Navy. In 2009, China also barred Google, Facebook and several other US internet groups — the start of a split of the technology world into two spheres that is now accelerating.

But one of the main reasons for the escalation in the rivalry between the U.S and China over the past few years — which some now see as the start of a new cold war — has been the surge in skepticism about Beijing across America’s political elite.

In late 2017, the Trump administration signaled it would take a tougher approach when it described China as a “revisionist power” in its first national security review. Few in Washington complained.

“That was a huge shift in mentality that has tremendous bipartisan support,” says HR McMaster, who was Mr. Trump’s national security adviser at the time.

Evan Medeiros, a former Obama administration White House Asia adviser, acknowledges that the label simply reflected the new reality in Washington. “When the Trump administration framed the US-China relationship in terms of strategic competition, many Americans were there already. They just hadn’t given it a name,” says Mr. Medeiros, who is a critic of how Mr. Trump has handled China. “Trump opened the floodgates and people said it’s time to call a spade a spade.”

“American elite and popular opinion has fundamentally changed. We have moved from balancing co-operation and competition, to competition and confrontation,” he adds.

Xi Jinping meets Magic Johnson with then Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa at a Lakers game in February 2012 © AP Source: The Financial Times

That does not mean a Biden administration would adopt the same policies towards China that would be seen in a second Trump term. In some areas such as subsidies to industry it might be tougher, working closely with Europe and other allies to constrain China, while on other issues, such as climate change, it might be more open to co-operation.

But it does mean that regardless of which candidate wins the election, the leader taking office in January will preside over a radically different US-China relationship than eight years ago, when Mr. Biden and Mr. Xi were both vice-presidents — or even four years ago.

“There is an existential competition between two countries with fundamentally different visions,” says Mike Gallagher, a Wisconsin Republican lawmaker and China hawk. “This is more complicated than the old cold war.”

A responsible stakeholder?

The more confrontational approach towards China may have been building for some time, but it still represents a dramatic shift.

In the four decades after Richard Nixon established diplomatic ties with Beijing, the US worked to bring China into the international system that it created after the second world war.

The project nearly collapsed at certain moments — notably after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. But it ultimately led to China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. Four years later, Robert Zoellick, deputy secretary of state in the George W Bush administration, urged China to become a “responsible stakeholder” in that system

Barack Obama broadly kept that approach, although his administration also started to hedge against Chinese assertiveness with a “pivot” that put more military assets in the Asia-Pacific.

But it was during his presidency that many lawmakers, officials, academics and companies became increasingly pessimistic that China under Mr. Xi would pursue real political or economic reform.

Donald Trump with HR McMaster, at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida, in February 2017 © Susan Walsh/AP Source: The Financial Times

Now, after four turbulent years of relations during the Trump administration, there are very few subscribers to the theory that engagement with China will lead the country to become more liberal.

“The responsible stakeholder era, which was a bipartisan approach, is over,” says Derek Chollet, a former Obama administration Pentagon and National Security Council official.

The list of U.S complaints is long and broad, spanning from cyber espionage to tensions in the South China Sea, human rights, intellectual property rights and market access for U.S firms in China.

There is also much less trust in Mr. Xi. In 2015 he stood in the White House Rose Garden and promised Mr. Obama that China would not militarize the artificial islands it was building in the South China Sea — but then proceeded to do exactly that at a fast pace.

More recently, the U.S has turned up the heat on China over its detention of an estimated 1m Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang region.

Across the political elite, there is consensus that large parts of the technology sector should be off-limits for Chinese investment because of its potential for military or espionage use. When the Trump administration strong-armed allies to cancel contracts with Chinese telecoms equipment maker Huawei earlier this year — a form of pressure that would have been unthinkable a few years ago — there was little disagreement in Washington, even if some Democrats believe the Trump administration has pushed the idea of economic ‘decoupling’ too aggressively.

A Chinese lesson during a government-organized visit in Kashgar, Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, China, last year © Ben Blanchard/Reuters Source: The Financial Times

“There is no question that Xi Jinping has taken China in a different direction . . . even a more authoritarian direction,” says Jeff Prescott, a China expert and senior foreign policy adviser to the Biden campaign. “The next president is going to have to recalibrate the relationship with China.”

After targeting Beijing during the election campaign, Mr. Trump actually entered office trying to mend fences with Beijing. He talked up his rapport with his “good friend” Mr. Xi who he feted over chocolate cake at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida in April 2017.

But the Trump administration soon started to take a more hawkish view, exemplified by the national security review later that year. Mr. McMaster says the document gave the green light to government agencies to toughen their approach. The justice department, for example, created a unit called the “China Initiative”, which has spent two years cracking down on espionage. “Their investigations increased dramatically after we announced the shift,” he says.

One senior Trump administration official says that until the president had stood up to Beijing, many people in Washington had assumed China was unstoppable and that U.S rhetoric and policy had developed a “defeatist smell”.

“You had senior U.S officials parroting Chinese Communist party jargon about a new type of great power relations that would allow for win-win solutions, by which they apparently meant China would win twice,” the official says.

Mr. Trump was cautious about alienating Beijing to avoid jeopardizing negotiations aimed at ending the trade war that he had launched against China. But that changed dramatically this year. After signing a limited “phase one” trade deal in January, he backed a slew of actions against China, over everything from human rights abuses in Xinjiang and the imposition of a draconian security law in Hong Kong, to threatening to ban social media app TikTok.

Some US officials say Mr. Trump is punishing China for not having done more to prevent Covid-19 from spreading to America, which he believes has hurt his chances of re-election. Many experts believe Mr. Trump would continue his current approach in a second term, unless he eased off on security to get a comprehensive trade deal.

Major realignment

The bigger question is how Mr. Biden, a former Senate foreign relations committee chairman who first visited China in 1979 and has been steeped in these issues for three decades, would treat China if he is elected.

Tom Donilon, former national security adviser to Mr. Obama, says Mr. Biden’s approach would have echoes of Dean Acheson’s “situations of strength”, a reference to the Truman administration secretary of state who argued that the US should work with like-minded allies.

“He sees the China challenge clearly and knows we need to put ourselves in the strongest possible position to meet it. There would be a major realignment with allies,” Mr. Donilon says.

Mr. Prescott says Mr. Biden would rally allies such as the EU to tackle the “aggressive and predatory challenges” from China — in contrast with the Trump administration’s approach. “We shouldn’t be insulting our friends. We should be working with them to address some of the challenges from China.”

Supporters of the Trump administration argue that it worked with Asia-Pacific and other allies to purge Huawei from their networks. But even some fans of Mr. Trump argue that he could have strengthened his hand with Beijing by working closer with allies.

Mr. Biden has rejected criticism that he would not be tough. His team includes advisers known for more hawkish views, such as Ely Ratner who was his deputy national security adviser during the Obama administration.

But Mr. Biden will also have senior advisers who believe that climate change is one of the biggest challenges facing the US — a position that might make them more open to co-operating with China.

Source: The Financial Times

Some in the national security community fear this could lead to a Biden administration making too many compromises. “I don’t think anyone thinks we’re going to turn the clock back, even with a Biden administration,” says Mr. McMaster. “But I am afraid that some Biden advisers will say we have to give on some things to get help from China on environmental issues.”

Mr. Gallagher says there was a danger that Mr. Biden would fall for the Chinese approach of dangling co-operation on climate as a “holistic bargaining chip” to get the US to take a softer approach on other issues. “If Biden tries to go back to the status quo and take a more accommodative approach, he’s going to get mugged by reality.”

Some Republicans warn a Biden administration will be too soft on trade. Marco Rubio, an influential Republican senator, told the Financial Times that Mr. Biden’s record on China over his career “makes clear his policies almost certainly accelerated the erosion of our nation’s manufacturing industry and offshoring of millions of good-paying jobs”.

Frank Jannuzi, who served as Mr. Biden’s East Asia adviser in the Senate for many years, says the former vice-president has a very sober view of China and believes it has changed for the worse.

“He has adopted a more muscular tone in public,” says Mr. Jannuzi. “This is a China where the Communist party is engaged in horrible human rights . . . in Xinjiang in particular,” he added. “Even those who were fans of engagement are adapting to the new China.”

Mr. Prescott says one “dramatic” difference between Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump would be on human rights. While the Trump administration this year imposed sanctions on Chinese officials over policies in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet, Mr. Trump himself has rarely spoken about human rights. John Bolton, his former national security adviser, wrote in his recent book that Mr. Trump effectively gave Mr. Xi a green light to detain the Uighurs.

“We should be standing up for our values and speaking out about democracy and human rights,” says Mr. Prescott.

Mr. Chollet says Mr. Biden would inevitably take a tougher approach than Mr. Obama. “There is going to be a more hawkish approach to China,” he says. “Even if Obama was FDR and going

In this 2016 photo, Chinese missile frigate Yuncheng launches an anti-ship missile during a military exercise near south China’s Hainan Island and Paracel Islands © Zha Chunming/Xinhua via AP Source: The Financial Times

Rigid response

Whether the superpower sparring escalates under whichever candidate wins will not just be a result of how these debates play out in Washington — it will also depend on how Beijing responds.

Some American officials believe the Chinese government recognizes it has pushed too far and helped produce a backlash in Washington.

“There has also been a substantial rethink on US-China policy in China,” says Mr. Donilon. “There is a comprehensive assessment under way in the Xi government. China is not going to forget the lessons of the last three years.”

Oriana Skylar Mastro, a China expert at Stanford University, says it was not clear how receptive Mr. Xi would be if the next administration were to try and change the relationship.

“Some say China will facilitate a reset and be nice while others say it will try to test the new president like it did with Obama,” says Ms. Mastro. “If Biden pursues a moderate strategy and China’s response is provocative and aggressive, it’s going to undermine those efforts. That’s how the China doves became China hawks.”

Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California San Diego, says the key is Mr. Xi himself. While she is critical of the Trump administration, she also levels blame at the Chinese president.

“The Chinese side brought a lot of it on themselves. I don’t think this is just dreamt up out of the forehead of McMaster or Matt Pottinger,” says Ms. Shirk, referring to the current deputy national security adviser and China hawk.

“If the door is a little bit open, does Xi have the good sense to walk through? I’m always looking for evidence of restraint and flexibility . . . but mostly I see rigidity. He has a very poor understanding of the west.”

Source: The Financial Times, October 9, 2020 | Demetri Sevastopulo