This May 24, 2019, photograph shows garment workers making men’s suits in a factory in Hanoi. Vietnam is doing its best to weave its way through the great power competition between China and the United States. (MANAN VATSYAYANA/AFP via Getty Images) Source: Stratfor Worldview

Vietnam shone in the geopolitical spotlight in 2019, writing an economic success story amid global uncertainty over trade, mediating between the United States and North Korea and becoming a key security partner for powers near and far. But as Vietnam prepares for an all-important leadership transition in January 2021, jockeying for influence among domestic political players and major outside powers will test the country’s political stability and strategic balance. Such a risk could complicate Vietnam’s investment climate at a time when competition is heating up to be the most business-friendly destination in the region.

Rising Prominence

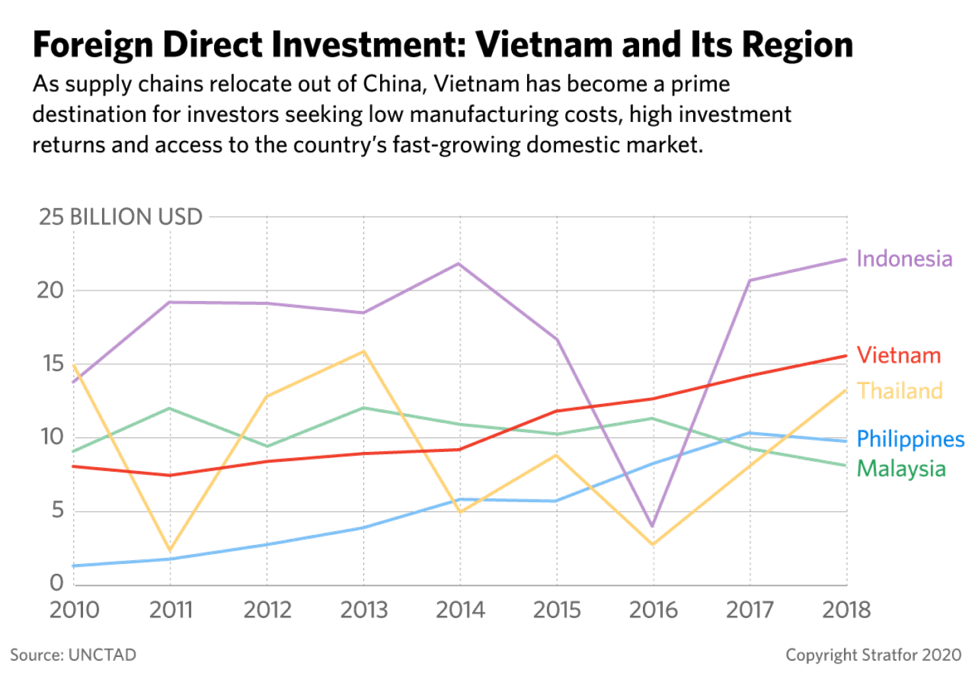

In an era punctuated by protectionism, Vietnam is making a name for itself as Asia’s next big success story. In just two years, the country has transformed itself from a low-end manufacturer into a major beneficiary of the U.S.-Chinese trade war, attracting many companies that sought to leave China because of U.S. tariff threats. That shift in supply chains has made Vietnam an investment magnet, fostering a long-overdue industrial upgrade and linking the country more closely with both Asian and global manufacturing powerhouses. In terms of growth, Vietnam’s projected rate of 6.8 percent for 2019 puts it well ahead of regional competitors like Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, where growth remains sluggish.

Vietnam’s growing economic strength has given the country newfound regional clout. Hanoi has taken a leadership role in regional initiatives among the countries of the Mekong River, while it has also become a more prominent actor in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In contrast, two of the region’s main powers, Indonesia and Thailand, have yet to emerge from their relative economic stagnation and inward focus. Likewise, Vietnam’s vocal opposition to China in the South China Sea (last year, Hanoi engaged in a five-month standoff with Beijing in the oil-rich Vanguard Bank) set it apart from other regional claimants like the Philippines and Malaysia, which took care to neutralize their tensions with China.

In an era punctuated by protectionism, Vietnam is making a name for itself as Asia’s next big success story. And Hanoi’s aspirations aren’t just confined to Southeast Asia. Deeply integrated into the global economy, Vietnam is a party to many new-generation free trade agreements, including pacts with the European Union and the wider Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. In addition, Vietnam has leveraged its advantageous location to cultivate security ties with virtually every major power, including China, the United States, Japan, Russia and India. In doing so, Hanoi is carving out a strategic space for itself by skillfully balancing among rival powers without alienating any of them. Such a multilateral approach also helps Vietnam insulate itself from the great power competition and meet its basic imperatives for economic development, independence and external security, thereby providing legitimacy for the ruling Communist Party.

Source: Stratfor Worldview

Charting a Route Between the Great Powers

Fundamentally, the factors that have contributed to Vietnam’s success story will continue in 2020 and, in all likelihood, beyond. Despite a limited trade deal between China and the United States, lingering uncertainties over global trade, China’s slowing economy and the East Asian giant’s rising labor costs will continue to shift supply chains and investment flows in favor of countries like Vietnam. Likewise, the great powers’ jockeying for influence in the Indo-Pacific will allow middle powers like Hanoi to continue reaping the benefits of relations with bigger actors. For Vietnam in particular, this will foster the space and capability to defend the country’s maritime sovereignty and claims in the face of an increasingly expansionist China.

Nevertheless, the roots of Vietnam’s success could create some problems for the country down the road. Indeed, the country’s deepening integration with the rest of the world has made it more vulnerable to volatility in global markets and disruptions to supply chains, particularly as Vietnam’s export-oriented economy is heavily dependent on foreign investment. Foreign investment also tapered off somewhat in the second half of 2019, providing a sign of the challenges to come for Vietnam. What’s more, rapid growth could also raise Vietnam’s labor and production costs, jeopardizing its competitive edge at a time when its infrastructure, supporting industries and labor skills still remain behind the likes of Thailand and Malaysia. But most critically, Vietnam’s rising manufacturing portfolio will continue to expose the country to twin risks from the globe’s two biggest powers: In the immediate term, Vietnam runs the risk of inciting a backlash from the United States, which doesn’t like others maintaining a significant trade surplus in bilateral trade. In the longer term, the nature of its growth will make the country more reliant on Chinese investments, thereby opening up the country more to the influence of its northern rival.

Source: Stratfor Worldview

In fact, despite Vietnam’s repeated efforts to reduce China’s economic influence, its reliance on the giant economy has increased over the years because it must import raw materials from China to manufacture its export products and because there are few alternatives to Chinese-built infrastructure in Southeast Asia. Hanoi, for one, cannot swing too close to Washington, lest it put itself in Beijing’s crosshairs, which is why it has been careful with such engagement and restricted its security cooperation with the United States to mostly training and military purchases. Likewise, while Hanoi has been debating about whether to resort to legal means to press Beijing in the South China Sea (as Manila did in filing an arbitration case against Beijing in 2013), the anger this would cause in China, as well as its inability to enforce any favorable ruling, will likely discourage Vietnam from pursuing such an option. Instead, Hanoi will leverage its possession of two key international positions in 2020 — its chairmanship of ASEAN and its non-permanent seat at the U.N. Security Council — to build up international support to counter China’s maritime aggression, even if that won’t meaningfully alter Beijing’s position.

Hanoi cannot swing too close to Washington, lest it put itself in Beijing’s crosshairs.

The Risks of a Political Transition

2020 will also be the last year before Vietnam embarks upon a transition in power next January at its party congress, which will elect the country’s top leaders for the following four years and beyond. Critically, the congress will almost certainly result in the retirement of the ailing incumbent party chief and Vietnamese president, Nguyen Phu Trong. There are plenty of questions about how party leaders will guide the country going forward, especially as Trong has exercised a great deal of power, in contrast to the collective leadership style favored by past rulers. Given the uncertainty over Trong’s successor, factional infighting could break into the open, resulting in a rapid shift in alliances and, more importantly, fomenting instability.

Despite his poor health, Trong could retain a tight grip and spearhead a transition to his allies, thereby guaranteeing Vietnam some political stability ahead of January 2021, but his possible incapacitation or political infighting will make the political transition far more turbulent. Such internal problems, meanwhile, could also result in an abrupt end to the country’s current pragmatism toward China, since Beijing’s expansion in the South China Sea has emboldened Vietnam’s China hawks, many of whom are younger leaders who do not have the same close links with the Chinese Communist Party that their elders do. Should these challenges escalate into a serious succession crisis, it could also jeopardize — at least temporarily — Vietnam’s investment climate, undermining the country’s appeal at a time when countries around the region are battling to throw their doors open to business the widest.

Source: Stratfor Worldview, January 3, 2020 |