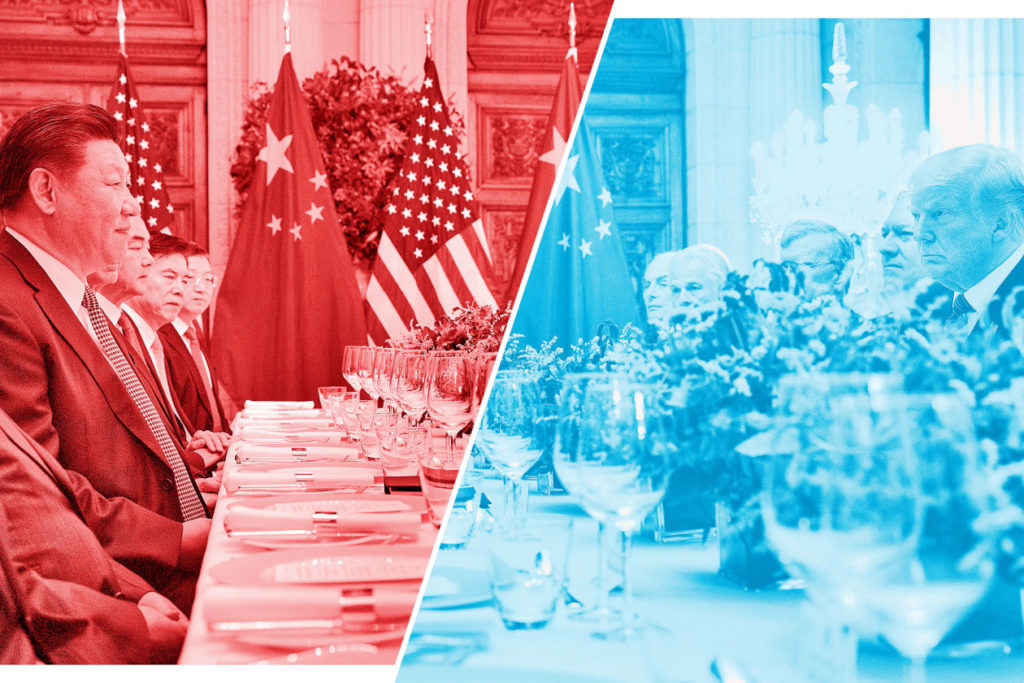

Investors have been on edge as the world’s two largest economies, the U.S. and China, tiptoe toward a trade agreement. Yet even if President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping reach a deal, a tariff peace won’t mean a return to the old ways of doing business.

The global system of trade is being realigned. A decades long drive toward freer trade across borders has begun to reverse. Globalization is being overwhelmed by populism, nationalism, and protectionism.

Brexit threatens to erect new trade barriers between the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe. India just moved to limit foreign operators selling goods online.

An eroding global consensus on free trade has led U.S. companies to modify their supply chains, often bringing suppliers closer to their end markets.

In the 1990s, global trade regularly grew at twice the rate of worldwide gross domestic product; since 2012, it has been rising only slightly faster than GDP, on average, according to the World Trade Organization. For this year, amid slowing global economic growth and rising barriers, the WTO has lowered trade expansion expectations to 3.7% from 4%, and said that first-quarter trade is slumping to 2010 levels.

Seaborne shipments to the U.S. fell 4.5% in February, including a 4.6% drop from the European Union. It was the first such decline in almost two years, according to Panjiva, a supply-chain data provider.

A recent Bain & Co. survey of more than 200 executives at multinational companies who do business in China found that 60% felt that the recent trade war had given them a chance to recalibrate their business strategies. Over the next year, 48% said, they expect to seek out new suppliers, and 42% expect to find raw materials elsewhere.

Corporate executives are adapting to a world where globalization is no longer the dominant force.

“I probably never would have said it was going to end, but I’m starting to wonder,” says Don Allan, chief financial officer at Stanley Black & Decker(ticker: SWK). “The trend seems to be heading that way. Countries are becoming more focused on protecting their world and less on how to work together as a global economy.”

Allan has been struck not just by the Trump administration’s antiglobalism agenda, but also by changes elsewhere, like the fragility of the European Union since the financial crisis.

“There’s definitely a major shift that has been going on for the past 10 years, and it has accelerated in the past five years,” Allan says.

The shift comes at a time of profound technological and political changes—including the advent of new robotic-manufacturing techniques, a North American energy boom, and China’s state-led push to sell higher-value goods—that have already led companies to reconsider and realign their global footprints. Those changes could eventually prove to be even more powerful than antiglobalization at rerouting global trade.

Investing in these trends will be tricky because they are likely to play out over decades. People can make money off supply-chain shifts by purchasing stocks that will benefit from new Chinese investment, including in renewable energy and batteries; focusing on countries, such as Vietnam, that will play a bigger role in global trade; and buying shares of companies that build robots used in manufacturing, some investors say.

While economists and politicians have promoted the idea of global trade for years, a slowdown and even a reversal in its pace wouldn’t be a historical anomaly. Globalization has actually risen and fallen in cycles, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch analyst Ajay Singh Kapur. “There is really no permanent trend, just lazy intellectuals confusing a long cycle for a perpetual-motion machine,” he wrote in a report last year that included a chart that extended back to the birth of Jesus.

Yet the rapid increase in trade in the second half of the 20th century made globalization seem to be an inexorable force. “The world is governed by market forces,” Alan Greenspan said in 2007. It seemed hardly debatable at that point. From 1950 to 2007, the value of global trade grew by 6.2% a year, on average, almost four times as fast as the global population rose. Transportation costs fell, regions specialized, manufacturers chased the lowest-cost inputs, and supply chains became longer and more complex.

Initially, the trend coincided with steady employment and wage gains for workers in developed economies. Those gains, however, deteriorated as manufacturers fled developed economies in the 1980s, seeking cheaper labor. In 1975, manufacturing represented over 20% of U.S. GDP and 22% of labor employment—today, it’s just 11% and 9%, respectively. After adjusting for inflation, incomes for nonsupervisory U.S. workers remain where they were in the late 1970s. Other developed nations have seen similar declines in manufacturing, coinciding with rising income inequality.

The political backlash against the perceived winners of globalization has manifested itself in events like Trump’s election and Brexit. Hoping to protect jobs, countries have sought to become increasingly self-reliant, putting up ever-higher barriers to trade.

Supply-chain decisions have rarely been so politically fraught. The Made in China label doesn’t disappear so easily into the seam of a U.S. company’s dress in an age of tariffs and angry presidential tweets. American-designed, Chinese-assembled iPhones have lost their status in Beijing, where consumers increasingly favor domestic brands.

Given the political implications, companies are mostly keeping quiet as they realign their supply chains, lest they invite pushback. Barron’s contacted more than 50 small and large ones that had applied for tariff exemptions or discussed changing their supply chains. Only two were willing to talk.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch analyst Andrew Obin says that “job creation (or lack thereof) is likely at the core of their ambivalence.” Even when corporations return production to the U.S., they might add more robots than humans.

And Trump isn’t the only one they risk alienating. “For companies shifting production out of China, they likely don’t want to advertise their moves, either,” Obin notes.

Such “reshoring” by U.S. companies is on the rise. More jobs were gained through reshoring than lost to offshoring in 2016, for the first time since 1970, says the nonprofit Reshoring Initiative. In 2017, employers announced decisions to bring a record 82,250 jobs back, up from just 3,221 in 2010. Preliminary numbers for 2018 show that reshoring announcements slowed last year, to 53,420—possibly a result of “uncertainty from the trade wars, dysfunction in Washington, and the dollar being up a little bit,” says the nonprofit’s founder, Harry Moser. But he calls the trend powerful and persistent. “It’s not just a trickle here or there.”

Many companies have found it attractive to regionalize all or some of their product procurement or assembly closer to their end markets. The rewards: cheaper and faster transportation, less complexity and risk of disruption, reduced inventory requirements, and the political benefits of making products where they’re sold.

GoPro (GPRO) is maintaining its Chinese factory to supply Asian customers. But it plans to move its manufacturing to Mexico from China for cameras bound for the U.S. “While the threat of tariffs served as a catalyst to improve supply-chain efficiency, this approach makes strategic sense, regardless of tariffs, and we expect to generate modest savings, to boot,” Its chief financial officer, Brian McGee, said on an earnings conference call last month.

Hasbro (HAS) started making Play-Doh at a factory in Massachusetts late last year, the first time it had produced the toy in the U.S. since 2004. Hasbro says lower transportation costs influenced the decision.

Solar-module maker SunPower (SPWR) is likewise working to move more production closer to its end markets. In industries with razor-thin margins, reducing shipping and other logistics costs can mean the difference between making or losing money.

SunPower’s core product is a solar module enclosed in glass. It sells for about $1 per watt to power plants and up to $2.25 to residential customers. As much as a dime of the cost is attributable to logistics.

“The bigger it is, the more the logistics cost it has, and the more likely you want to regionalize production,” SunPower CEO Tom Werner tells Barron’s.“The panel tends to be the first thing solar companies look to regionalize, to bring it closer to end demand.” SunPower has been expanding operations in Mexico for products it sells in the States. It even bought a small U.S. solar manufacturer last year.

Source: Barron’s, March 18, 2019 | Avi Salzman and Nicholas Jasinski