Chinese leaders used to worry about when economic growth might slip below the level of 6 percent to avoid job losses and social unrest. But now, as they face the prospect of the first quarter of zero or negative growth since the chaos of Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution, they are closely watching the numbers of trucks rumbling in and out of places such as Qian’an.

The district is home to some of the largest mills in Tangshan, an industrial hub east of Beijing in Hebei province that produces about 10 percent of the country’s steel and is crucial to global markets for the metal. Trucks enter Qian’an carrying coking coal and iron ore, and exit loaded with steel.

Workers at Qian’an steelworks of Shougang Corporation in Tangshan, China © Xiaolu Chu/Getty

If the district’s mills can raise production quickly — as extreme measures taken to contain China’s coronavirus epidemic are eased — it will suggest that the short, sharp shock to the world’s second-largest economy since January might well be followed by a second-quarter rebound — the much vaunted “V-shaped recovery”.

Alternatively, the government’s efforts to restart activity in places such as Qian’an could lead to a rise in new infections, which would then lead to new containment measures and an even greater economic aftershock. President Xi Jinping doubled down on this gamble on Tuesday, when he made his first visit to Wuhan in central Hubei province, where the epidemic originated in December.

These two starkly different scenarios explain why large trucks are about the only things entering and leaving Qian’an freely. Owing to its critical importance to the steel industry, the district has been placed under some of the strictest quarantine measures outside Hubei province.

Supermarkets in Qian’an are closed and all residents have been asked to regularly report body temperatures and flu-like symptoms. Steelworkers cannot leave their mills and family members cannot visit them.

With the exception of one mill that recently suffered a coronavirus outbreak, after one of its employees was infected at a village banquet, traders say all industrial firms in Qian’an are back up and running, albeit below normal levels of production. The question now is how much steel can they sell.

“There is no demand, especially in northern China,” says Zhang Ying, a trader who regularly deals with Tangshan’s mills. “The best we can do is sell a very small portion of the steel to southern regions or some priority construction sites that are up and running.”

A worker wearing a mask works on a production line manufacturing bicycle steel rim at a factory in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, China, last week © China Daily/Reuters

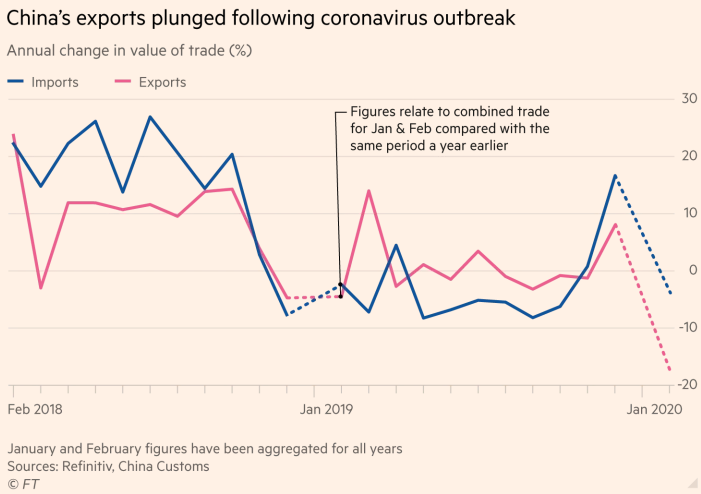

The disease’s transformation into a global epidemic — with case numbers climbing rapidly in countries as far afield as South Korea, Iran, Italy and the US — means China’s economy might recover only to discover that many of its largest trading partners remain ill, damping demand for its exports.

From a political perspective, it will be impossible for Mr. Xi, China’s most powerful leader in decades, to disown the economic consequences of the coronavirus calamity. Mr Xi said he was in charge of the epidemic response as early as January 7 — two weeks before its seriousness was first publicly recognized by the ruling Communist party and central government officials. That, in turn, has raised questions about the vulnerability of China’s increasingly authoritarian party-state.

“The party propaganda machinery has unwittingly admitted that Xi was responsible for the fiasco,” says Steve Tsang, head of the China Institute at Soas in London. “The changes Xi has made to the operation of the party-state have not strengthened its capacity to act in order to pre-empt a crisis.

An adviser to senior officials in Beijing agrees. “This virus crisis was really 70 percent human error [attributable to] the leadership,” he says.

Some economic projections make sober reading for China’s leadership. Bert Hofman, director of the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore, predicts that “first-quarter growth year on year may well be negative, between -2.0 and -6.5 [percent]”.

Such a sharp downturn, if it continues beyond the first quarter, could in turn imperil what the Chinese government has long seen as the principal function of strong growth in gross domestic product — urban job creation, targets for which are typically set at 10m or more new jobs each year.

“Services and consumption now contribute more than half of China’s GDP,” says Mr. Hofman, a former China country director for the World Bank. “The economy is therefore more sensitive to a drop in domestic demand resulting from the epidemic and the government’s control measures. It is harder to make up lost ground in services than it is in manufacturing.”

In a short-term downturn, capital expenditures are only delayed. But some spending, such as lost box office revenues over the Chinese new year period — $3.9m this year compared with $1.5bn in 2019 — will never be recouped.

Amid signs that Beijing’s public health measures are beginning to contain the outbreak, officials from Mr. Xi down are accentuating the positive. “The fundamentals of the economy will remain strong in the long run,” Mr. Xi assured the presidents of Chile and Cuba during recent phone calls.

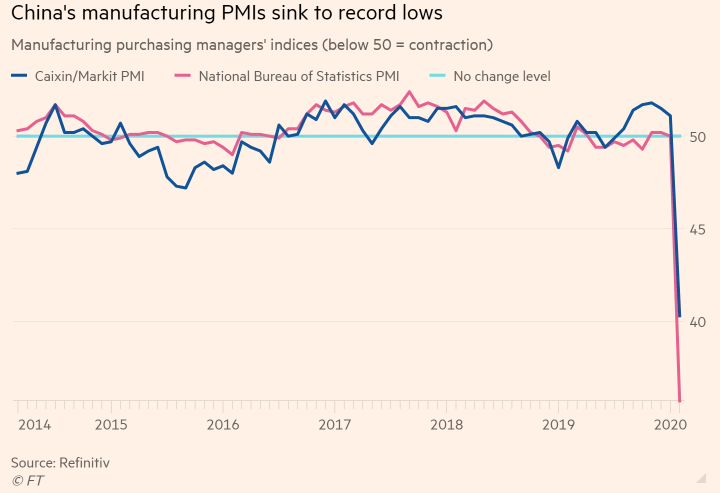

When the National Bureau of Statistics released a record low figure for its official purchasing managers’ index on February 29, it added — in an unusually political aside — that “under the party’s firm leadership with Xi Jinping at the core, the virus is coming under control . . . and market confidence is steadily recovering”.

In a widely circulated report on Chinese social media, Zhang Anyuan, chief economist at Citic Securities, criticized analysts who have projected that first-quarter growth might only fall to 4 or 5 percent year on year.

“They look at the heavens to divine the future and assert that [the economy’s] medium and long-term outlook is still good,” Mr. Zhang wrote. “If such head-slapping political declarations become the basis for strategic decision-making, they will cause as much harm as the early misjudgments [about the seriousness] of the epidemic.”

A worker wears protective clothing as she watches over customers in a Beijing supermarket last week © Greg Baker/AFP/Getty

“How is it possible”, Mr. Zhang added, “for the economy to achieve positive growth in the first quarter when more than 1bn people stayed at home for nearly a month?”

Aside from the NBS’s February PMI figure, and a 17 percent annual fall in the value of January-February exports reported by China’s customs administration on Saturday, most official data for the period will not be released until later this month. Until they are, optimists and pessimists alike can pick and choose from a host of contradictory anecdotal information — as well as various ad hoc indicators of economic activity — to bolster their arguments.

Government officials typically cite data suggesting that the vast majority of companies have returned to work. But analysts caution that the figures reflect only the number of companies which have approval to operate, meaning that many businesses may still be operating at far below their normal rates.

According to a China Merchants Bank index that uses satellite imagery to track night-time activity, as of Monday just under 60 percent of 143 major industry sites across the country had resumed operations.

G7 Networks, a start-up that collects GPS data from about 20 percent of China’s cargo vehicles, has been releasing a daily tally that shows a rapid recovery in full-truck deliveries usually made by major companies, but only a gradual uptick for shared consignment shipments, which tend to be used by smaller businesses.

Compared with early February when this data looked “extremely bleak”, big deliveries to factories and construction sites have rebounded to about 60 percent of peak November levels. But smaller shipments are only running at about 26 percent “not because there are no drivers, but because there are no orders”, says Sun Fangyuan, a G7 market director, adding that consumption had started to pick up in the past week.

In the face of languishing commercial activity, southern Guangdong province last week expanded its 2020 development plan to include Rmb100bn ($14bn) worth of new public health, rural development and shantytown reconstruction projects, while eastern Zhejiang province added 100 new railways, roads and disaster relief programs. Seven other provinces have recently announced investments worth Rmb25tn, although analysts at brokerage Everbright Sun Hung Kai estimate that only about Rmb3.5tn will be allocated this year.

Linda Liu, who runs a kitchenware manufacturer in Yiwu 280km from Shanghai, sources stainless steel from domestic suppliers and says things are improving, in part because of local government subsidies to pay migrant workers’ transport costs for their journeys back to work.

“My factory restarted operations [in] February and Yiwu’s international trade market [a major wholesale center] has also reopened,” she says. “So far half of our workers and salesmen are back at work. My suppliers haven’t returned to their previous production levels, but we have orders and inventory from late last year so we’ve still got something to do.”

Traditionally when Chinese demand slumps, steelmakers simply export more. But that might not be an option when markets such as South Korea are contending with their own virus outbreaks, says Sebastian Lewis, an analyst at S&P Global Platts.

“Margins at mills are going to take a hit,” he adds, but downstream industries like property are a bigger concern. “In the past, the government might have let some companies go to the wall to help industry restructuring, but it’s now got to the point where employment, stability and getting the economy going again comes first.”

Shen Jianguang, chief economist at JD.com’s financial services subsidiary, believes the initial hopes of a rebound after the first quarter are fading as the epidemic’s impact on supply chains and on consumption becomes clearer.

“Quarter on quarter, there will for sure be a [second quarter] rebound, but for [annual economic growth] to be above 6 [percent] for the year, there will need to be a coordinated policy of fiscal and monetary support to induce and encourage people to spend,” he says.

In an analysis of listed companies’ financial statements, Mr. Shen found that about half of the hotel food and leisure groups on specialist technology stock exchanges in China face short-term liquidity risks. Separately, he estimates that annual earnings for companies on the main stock exchanges will fall by about 30 percent on average.

He predicts that many retail and consumer firms will find it almost impossible to recover: “It’s very hard to compensate for tourism. It’s hard to have another holiday like Chinese new year.”

On March 1, China’s central bank and banking regulator announced that small and medium-sized enterprises could apply to delay debt and interest rate payments due in the first half of the year. The SMEs’ lenders, in turn, will be able to postpone formal designations of the loans as non-performing. A day earlier HNA, a private-sector aviation and tourism group based in southern Hainan province, said it had failed to “resolve” financial risks exacerbated by the epidemic and effectively declared itself a ward of the state by appointing two provincial officials to key posts.

Wu Hai, a service-sector entrepreneur who runs a chain of 50 karaoke parlors in Beijing, says his company has about Rmb12m cash on his balance sheet. He believes he could keep the parlors closed until the end of August if necessary without going bankrupt, thanks in part to a five-month government exemption on social insurance payments granted to SMEs.

“The central bank and finance ministry are offering banks’ discounted government loans to lower financing costs for SMEs,” he says. “But banks cannot just lend to small businesses without assessing risks.”

A man walks on an empty street in Wuhan last month © STR/AFP/Getty

Qin Nan, whose Beijing-based company makes and installs air purifier systems, discovered in February that getting the financial help supposedly on offer to SMEs was not straightforward. When he asked his bank to delay loan repayments it refused, saying it has a limited quota for repayment delays. Mr. Qin is now trying to renew the loan but can only do so if he can find a credit company willing to guarantee it.

More ominously for China’s cash-strapped local governments, which in 2018 raised almost 40 percent of their total revenues from land sales, house sales across China’s 30 largest cities fell more than 80 percent in the first three weeks of February compared with the same period last year, according to official data. This has hit developers, which have tried but largely failed to entice buyers with online deals and steep discounts. Land sales are now running at less than a quarter of average levels, according to China Merchants Bank.

All of these unprecedented pressures, and Beijing’s responses to them, are shaping up to be the ultimate stress test of the Chinese party-state that Mr. Xi now dominates.

“How long will it take to restart the economy? It can’t just go from zero to full speed,” says Bilahari Kausikan, a former Singaporean diplomat who also points to the risk from the epidemic’s global spread.

“As [new case numbers in] China plateau, things are getting bad in the US and Europe. A synchronized slowdown will affect China. it’s not a universe unto itself.”

Source: The Financial Times, March 10, 2020 | Tom Mitchell, Christian Shepherd and Sherry Fei Ju