A year is a long time in Tinseltown. At the end of 2016 Wang Jianlin, the chairman of Dalian Wanda, the Chinese property, retail and entertainment group, appeared on the front of the film industry bible The Hollywood Reporter, to reveal a startling interest: he wanted to invest in each of the big six movie studios with the aim of eventually acquiring one.

One of China’s richest men, Mr Wang, known to employees and colleagues as “the chairman”, had already earned a reputation in Hollywood for big talk — and for having the firepower to back it up. Wanda had spent $2.6bn on the AMC cinema chain and $3.5bn on Legendary Entertainment, the company behind movies such as Godzilla and Pacific Rim. Those deals were part of a string of investments by Chinese entities in US entertainment, part of a co-ordinated push under President Xi Jinping to change the country’s image. Wanda was one of its prime exponents: in an April interview with the Financial Times Mr Wang said the company contributed “significantly” to the rise of Chinese “soft power and cultural influence”.

But fast forward 12 months and Mr Wang and his fellow countrymen are in retreat from Hollywood, part of a Chinese crackdown on capital flight. Paramount Pictures’ $1bn three-year film financing deal with Huahua Media, a Chinese entertainment group, has been scrapped, which the Viacom-owned studio said was due to “recent changes to Chinese foreign investment policies”. Wanda’s planned $1bn purchase of Dick Clark Productions, the company that produces the Golden Globes awards show, was also pulled. Mr Wang, meanwhile, has not been seen in Hollywood for several months: in the summer Wanda denied rumours that he had been forbidden from leaving China.

Once considered the perfect backdrop to project soft power, China appears to have soured on expanding its presence in US film. Jeffrey Katzenberg, the former DreamWorks Animation chief executive — and who was instrumental in forming Oriental DreamWorks with Chinese partners — says there has been a noticeable change.

Jiang Wen, left, and Donnie Yen in ‘Rogue One’. Many big budget US movies now feature Chinese stars

“There was this shift in policy to a more nationalistic approach,” he told the FT. As well as the crackdown on capital outflows, he says China’s soft power ambitions have been superseded by its One Belt, One Road initiative, which seeks to build infrastructure that will join China to Central Asia, Europe and Africa by land and sea.

The change in approach has been keenly felt in Hollywood, where Chinese entities “were basically giving away free money”, according to one senior film executive. That tap has now been turned off — at least, for now.

The question that remains is after striking a flurry of deals and tie-ups with the US movie industry, did China get much of a bang for its buck?

Jeffrey Katzenberg, the former DreamWorks Animation chief executive who helped formed Oriental DreamWorks © Getty

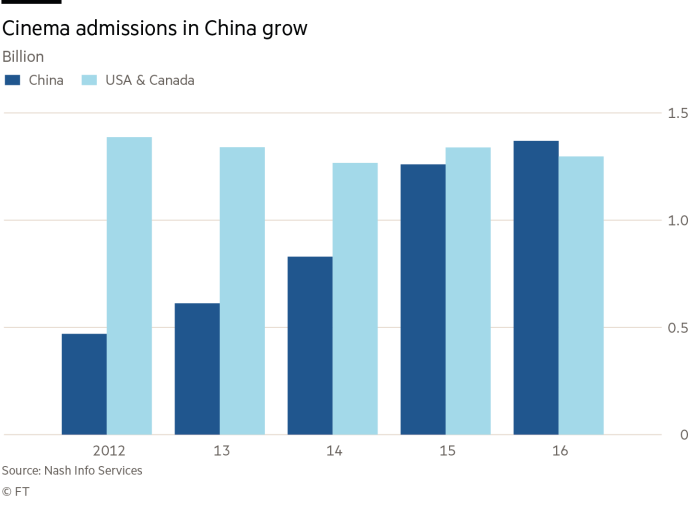

Despite the recent change in policy, China’s influence in Hollywood has risen sharply over the past decade. “While there has been a shift in capital flows you would be hard pressed to find a producer in Hollywood willing to make a film that portrays China negatively,” says Aynne Kokas, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the author of Hollywood Made in China. This development reflects the size of China’s cinema market, which has grown rapidly in line with the urbanisation of the country, according to IMAX chief executive Richard Gelfond. The big screen operator has 482 screens in China.

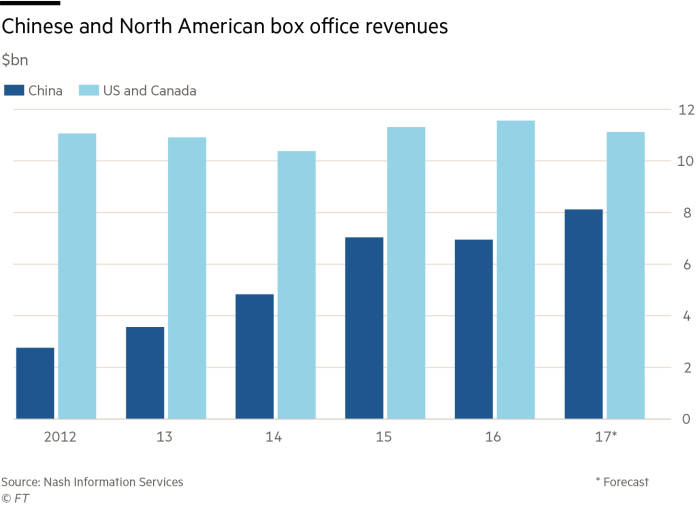

He points to the size of the market 15 years ago when China was “a very small part of the global box office”: now it rivals the US, the world’s largest theatrical market. China’s box office takings grew an average of 35 per cent a year in the past decade according to data from EntGroup, the consultancy, although growth slowed to 3.5 per cent in 2016, generating Rmb45.3bn — or almost $7bn — and is set to fall again this year. The North American box office, by contrast, was worth about $11.4bn in 2016.

Hollywood producers do not want to risk falling foul of the country’s censors and have their films denied access to such a big market. “China is incredibly important in terms of whether Hollywood movies succeed,” says Dede Nickerson, the founder of Infinity Pictures in Beijing. “It is not uncommon for US films to have better box office results in China than in the US.”

Matt Damon in ‘The Martian’: a film that portrays American and Chinese characters working together

The biggest studios, such as Walt Disney, Warner Brothers, Universal and Sony Pictures, make films that portray China and Chinese characters in a positive light. Many big budget US movies now feature Chinese stars, often in supporting roles: Jiang Wen and Hong Kong’s Donnie Yen both starred in Rogue One, the recent Star Wars prequel, while Chinese actress Jing Tian appeared in this year’s Kong: Skull Island from Wanda’s Legendary — albeit in a role with barely any lines.

The greater visibility of Chinese characters in Hollywood storylines “is much more driven by economic concerns than by soft power”, says Mr Gelfond. Marketing to the Chinese audience is not just about selling tickets, he argues. “It’s the merchandise and other ancillary revenue available there.”

Hollywood-made science fiction films increasingly portray China and the US as having harmonious, co-operative relations, despite the growing geopolitical tensions between the two countries. Professor Kokas points to recent movies such as Arrival and The Martian, two sci-fi films that portray American and Chinese characters working together. “Ultimately they are very positive depictions of US-China collaborations which does not reflect what happens in the real world,” she says.

China has a history of taking offence at films that tackle politically sensitive topics or which portray the country in a contentious light. Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet, both released 20 years ago, outraged censors and were banned in the country.Walt Disney produced the Martin Scorsese-directed Kundun, a story of the Dalai Lama that infuriated the Chinese government. Given that the group planned to develop theme parks and release more movies in China, it then hired Henry Kissinger to lobby officials in Beijing to repair relations.

Actors that have starred in offending movies found that their other work would not be screened in China. Brad Pitt was reportedly banned from China after his 1997 film Seven Years in Tibet, although the ban appeared to have been lifted by 2014, when he visited the country with his wife, Angelina Jolie.

Richard Gere’s criticism of China had a similarly detrimental effect. A supporter of Tibetan independence and an ally of the Dalai Lama, Gere said in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter this year that his political views had limited his work. “There are definitely movies that I can’t be in because the Chinese will say, ‘Not with him’. I recently had an episode where someone said they could not finance a film with me because it would upset the Chinese.”

Billionaire Wang Jianlin, chairman and president of Dalian Wanda © Bloomberg

Risking access to such a vast market means the biggest studios are much more reluctant to make films that even hint at criticism of China. “For the China market you self censor because of its size,” says Stanley Rosen, a China specialist at the University of Southern California. “But there has been a backlash in

He mentions the 2012 remake of the 1980s hit Red Dawn. In the original film a group of Midwestern teenagers fight a rearguard action against a Soviet army that has invaded the US. In the remake, the invading army was originally written as Chinese but after shooting had started the film’s producers swapped Chinese flags and other insignia for North Korean ones.

Chinese companies have tried to use their US investments to shift perceptions, although the results have been more mixed. On paper, Wanda’s ownership of AMC, America’s largest cinema chain, should have smoothed the way for even more positive big-screen portrayals of China. “When you know that the largest theatre chain in the US has a Chinese owner is there an inclination to make more favourable product that plays to their audience?” says Mr Gelfond at IMAX. “I would say there would be.”

But Wanda’s strategy of marrying content production, via its ownership of Legendary, with the distribution of AMC does not appear to have paid off. It spent an estimated $150m producing The Great Wall, a fantastical epic starring Matt Damon about hordes of monsters descending on ancient China. But while the movie performed quite well in China, it flopped in the US. AMC’s affiliation with Legendary “may have discouraged” rival US cinema chains from “pushing” the movie “as hard as they might have”, says Mr Gelfond.

The film also underscored the limitations of Hollywood-China tie-ups. “It was ultimately an attempt to tell a universal story,” says Prof Kokas. She mentions the criticism of the casting of Matt Damon in the title role: US cinemagoers have become increasingly vocal about so-called “whitewashing”, or the use of white stars in roles that should have been taken by ethnic minority actors. There have been similar criticisms levelled at Doctor Strange. Tilda Swinton was cast as the elderly Tibetan monk in the adaptation of the Marvel comic.

“The Great Wall tried to fit Matt Damon’s character into a Chinese film and that created a backlash in the US,” says Prof Kokas. “It shows the provincial nature of Hollywood studios, which also tends to be a barrier to collaboration with Chinese companies and developing Chinese source material.”

There are some signs of attitudes changing. Disney recently announced it was producing a live-action version of its 1998 animated hit Mulan and has cast Chinese actress Liu Yifei in the lead role.

China’s soft power push into Hollywood led to the forging of new alliances with US partners. But not all of these deals have gone smoothly. Universal Pictures, the movie studio owned by Comcast’s NBCUniversal, is on course to offload its stake in Oriental DreamWorks, the animation group, following disagreements over strategy with one of the company’s other main backers, Li Ruigang, the media entrepreneur behind the China Media Capital fund.

Universal inherited its 45 per cent stake in Oriental DreamWorks, widely regarded as the flagship joint venture between Hollywood and China, when it acquired Mr Katzenberg’s DreamWorks Animation — the studio behind the Shrek and Kung Fu Panda films — in 2016 for $3.8bn. But it quickly became clear that Universal had a different vision to Mr Li. “I am focused more on China and less globally while they want to make films in China for the world,” he told the FT in September.

Li Ruigang, the media entrepreneur behind the China Media Capital fund © Bloomberg

China’s retrenchment in Hollywood might still have some way to go: two industry executives said they had been told that Wanda was under pressure from China to reduce its exposure to film and sell AMC. The company declined to comment but AMC recently confirmed that it had been approached by several potential acquirers.

Despite this, Mr Katzenberg believes that Hollywood will continue to strive to be part of China’s growing domestic market. “It will surely become the largest movie market in the world,” he says. “Hollywood can’t ignore it . . . you go where the customers are. You ignore it at your peril.”

Source: Financial Times I December 26, 2017 I Matthew Garrahan & Charles Clover