BEIJING—China’s birth rate fell to its lowest level in the country’s modern history, hastening the aging of the population and the shrinking of the workforce, despite the government’s efforts to reverse the trend.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Already, nearly a fifth of China’s population is age 60 or older. A shrinking working-age population can dent the economy through lower productivity and higher labor costs, while an increasing number of elderly pushes up health-care costs. South Korea and Japan are facing similar problems but on a much smaller scale.

“The lesson from other East Asian countries is that once the birth rate declines, it’s hard to get back up,” said Julian Evans-Pritchard, an economist at Capital Economics, an economics research firm. “China’s going to have to get used to a continuous drag on growth from shrinking employment.”

Economists say China’s economy is on pace to grow around 6% this year. Capital Economics estimates that by 2030 population changes will shave half a percentage point each year off China’s gross domestic product growth rate.

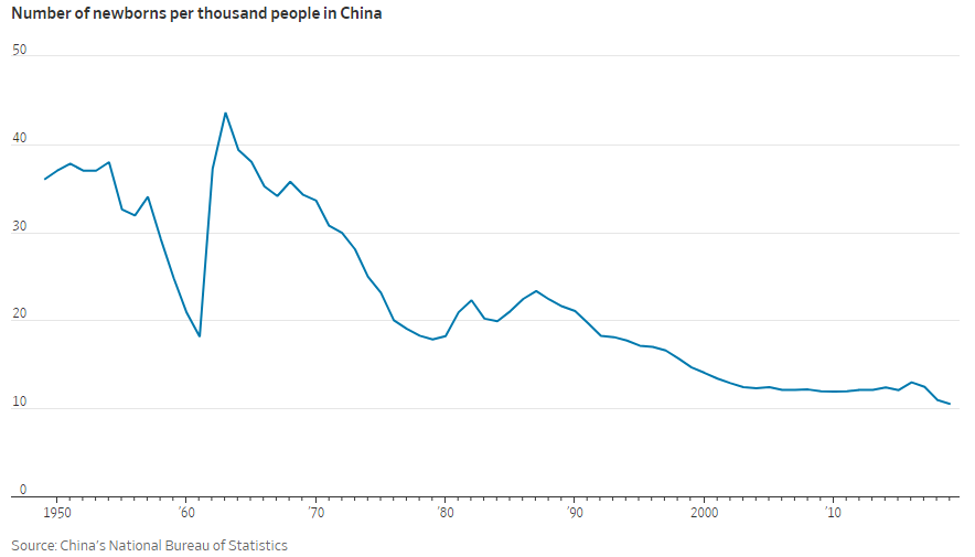

There were 10.5 new births per thousand Chinese people in 2019, the lowest rate since the Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, according to official data released Friday. The ratio has slumped for three decades following a small uptick in the 1980s and is much lower than it was in 1961, when China suffered one of history’s worst famines.

The country’s number of live births fell 4% to 14.65 million in 2019, a third consecutive year of declines.

Chinese women are having fewer babies as cultural expectations shift and the financial burden of living in cities skyrockets. They are becoming more educated and forming different views on career and marriage, with some putting off childbearing until later, or not having children at all.

China’s social-welfare system lags behind that of rich nations, leaving parents with greater responsibility for child care and education. Discrimination in the workplace over pay and recruitment can also discourage women from having children.

Views on childbearing are especially stark in big cities. Kang Juan, a 41-year-old editor of a financial publication in Beijing, has decided that a child would create an unnecessary burden. “I won’t have children unless there is an unplanned pregnancy,” said Ms. Kang, who is single.

Ms. Kang said she saw many of her female colleagues forced to accept lower salaries after having children. “Having children will definitely hinder your career development in China,” she said.

In hopes of relieving demographic pressures on the economy, the government began allowing families to have two children in 2016, after economists warned that the strict one-child birth-planning program implemented in 1980 was creating a demographic time bomb. The country’s workforce began shrinking eight years ago.

A family waits for a train in Beijing. PHOTO: REN CHAO/ZUMA PRESS Source: The Wall Street Journal

The move hasn’t had the expected impact: While Chinese newborns increased in 2016, they have dropped steadily since.

The burdens of big-city life are putting a pause on David Yan and his wife’s plans to have a child. Mr. Yan, 31, said the couple want to take the next few years to secure a steady income before deciding when to have a family. “A kid requires fees for nursery, school, tutoring and more,” he said.

The couple live in a shoebox unit so they can be in central Beijing. They haven’t been able to upgrade to a bigger apartment because property prices have soared. Mr. Yan lost his job in October, when the small financial firm he was working for went bust. His wife works at a state-owned company.

Some researchers have questioned the reliability of China’s official population data. Private estimates suggest that China had fewer babies than official data indicate and that the population started shrinking by 2018, despite official data that showed the population expanding.

Demographers and economists have also been wary of China’s official death numbers, which have stayed unchanged at roughly 9 million a year since 2006.

There have been irregularities in official local birth data, too. For example, in the southwestern megacity of Chongqing, the number of newborns dropped 44% in the first five months of 2019, according to figures from the local health authorities, but jumped in June. Births that month exceeded the total in the previous five months. Late last year, local health authorities said data from early in the year hadn’t been transferred properly because of an upgrade to their information system and was eventually added to June’s tally.

The annual number of newborns in China was inflated by up to three million each year in the decade leading up to 2010, estimates James Liang, an advocate for more aggressive birth-promotion policies and chairman of Nasdaq-listed online travel service provider, Trip.com, formerly known as Ctrip.com.

Mr. Liang based his newborn calculations on fertility rates from census data in 2010, the most recent year for which the numbers are publicly available. That year, on average, a woman would have 1.18 children over her lifetime. Some researchers said the rate has dropped to as low as 1.05 in recent years.

Mr. Liang’s company is trying to make it easier for female employees to plan families by offering benefits such as covering the costs of freezing eggs.

—Liyan Qi and Grace Zhu contributed to this article.

Source: The Wall Street Journal, January 18, 2020| Chao Deng