“One country, two systems”—the awkward formula under which freewheeling Hong Kong has survived in China’s statist economy—has always been viewed with deep ambivalence in the ultra-capitalist territory and Beijing alike. Yet maintaining the arrangement is paramount to the success of both.

Relations between Beijing and the semiautonomous city now face their biggest test since the U.K. handed back the territory in 1997, as protests sparked by legislation that would have permitted extraditions to the mainland mushroom into a wider movement. Many fear that Beijing could ultimately intervene directly. Strident official rhetoric comparing the more violent protests with terrorism and accusing participants of being influenced by foreign “black hands” raises the stakes of backing down.

Still, direct intervention would be hugely risky for Beijing—not just politically, but also for China’s global economic ambitions, financial stability, and ability to attract foreign capital and expertise to fuel its own growth.

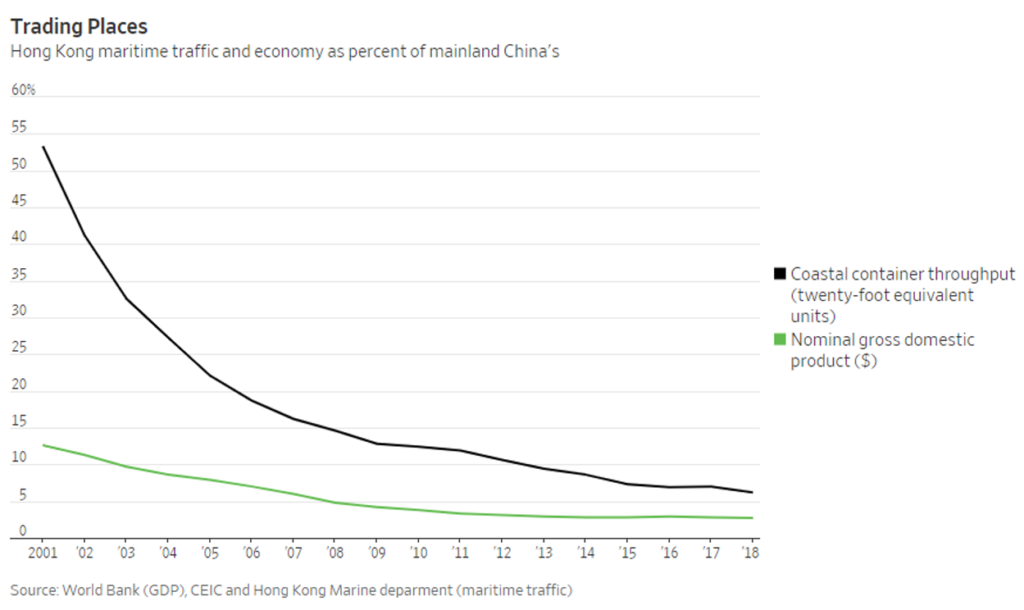

On pure size, Hong Kong carries far less heft relative to the mainland than in the late 1990s. Its output was 3% as large as the mainland’s in 2018, against nearly a fifth in 1997.

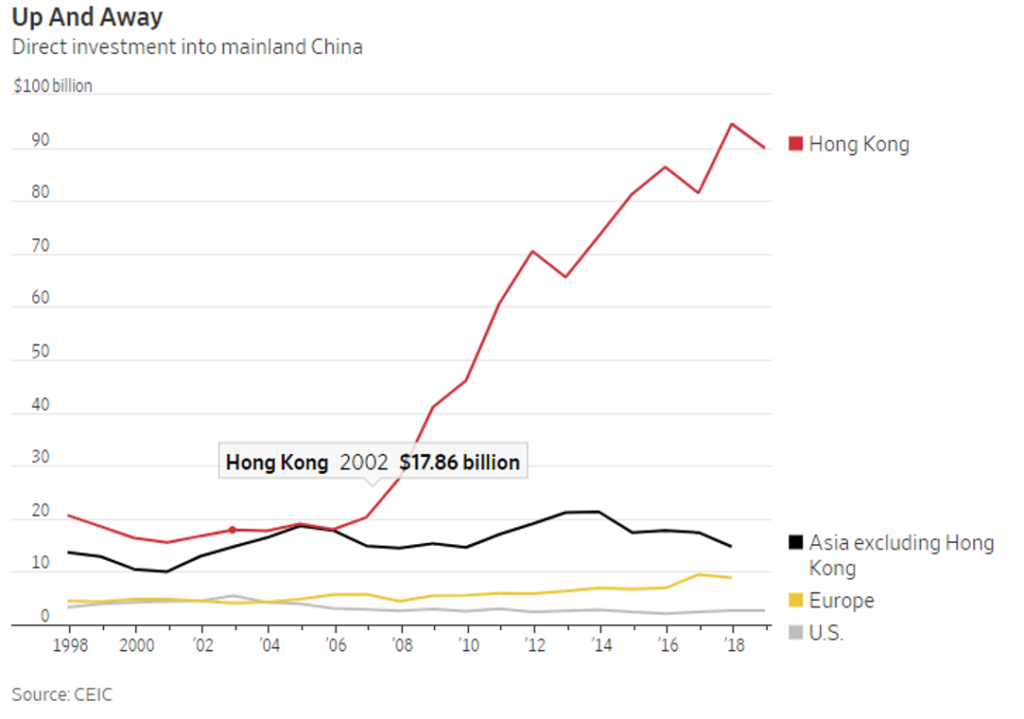

But the city remains central to China’s economy. It is its main interface with global capital markets, the conduit for most foreign direct investment in China, and a big source of assets sitting on Chinese banks’ and property developers’ balance sheets. Sudden disruption to all this would have unpredictable—perhaps unmanageable—effects on China’s own rickety financial system.

Moreover, China’s own reluctance to push forward with reforms has only raised the value of Hong Kong as a buffer between the mainland and global capital markets. Following the Shanghai stock-market crash and Chinese currency crisis of 2015, China has progressively tightened its grip on capital flows into and out of the country. The “connects” between Hong Kong financial markets and mainland markets are the easiest pathway for foreign investors to buy Chinese assets, and the offshore yuan market centered in Hong Kong offers Beijing additional ways to discourage currency speculators.

While Hong Kong is legally part of China, the People’s Republic guaranteed it a “high degree of autonomy” until 2047 as a condition of the 1997 handover. It has its own Western-style legal system, currency and trade agreements. The U.S. and other major powers treat it as a separate legal jurisdiction. Should the U.S. reconsider that status, as legislators have threatened in the event of aggressive action by Chinese authorities, Hong Kong could become subject to U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods, technology export controls, or visa changes.

Even before protests shook Hong Kong this summer, there was widespread fatalism about its future as a financial and trade center. But Beijing’s dependence on the “special administrative region” runs far deeper than it might appear. This series takes an in-depth look at the economic stakes for China and Hong Kong in the current upheaval.

The hit to Chinese trade would be manageable. Mainland China’s coastal container port throughput, which was less than twice as large as Hong Kong’s seaborne throughput in 2001, is now more than 10 times as big.

But the financial impact of a loss of confidence could be severe. Chinese investment inflows into Hong Kong over the past two decades have been gargantuan, which is one reason why property there is so pricey. Should capital flight tank the property market—or undermine the Hong Kong dollar’s longtime peg to the greenback—Chinese property developers and banks would likely sustain serious damage. The impact could be magnified if the yuan simultaneously came under pressure, or international political pressure curtailed Chinese companies’ ability to refinance dollar debt.

Even assuming the immediate financial turbulence could be contained, any change in the status quo would cause severe long-run damage. Around 60% of foreign direct investment into China flows through Hong Kong, although much of this comes from offshore Chinese companies.

Investors like funneling cash into China through Hong Kong because the city’s legal and regulatory system—combined with the substantial Hong Kong footprint of wealthy Chinese and Chinese companies—means investors have real recourse in the event of disputes. Singapore and Shanghai simply can’t offer the same combination of rule of law, open capital account, stable currency and Chinese “skin in the game.” If investors conclude Hong Kong is no longer a reliable base for jumping into China, foreign investment into the nation as a whole may take a substantial, permanent hit. On Friday credit ratings company Fitch, citing deteriorating international perceptions of governance and the rule of law, downgraded Hong Kong for the first time since 1995.

One reason China bounced back after the trauma of the massacre of student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 is that foreign leaders still assumed Beijing was committed to “reform and opening.” Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping had strong credentials as a reformer, despite his role in the crackdown, and liberalization kicked off again in 1992 with his “southern tour.” This meant sanctions were mostly moderate or short-lived.

These days, China carries much greater economic weight, but shows little sign of embracing further liberalization. So far, European and other Asian nations haven’t presented a united front with the U.S. on trade relations, but a tragedy in Hong Kong might change their calculus.

Hong Kongers have the most to lose if matters deteriorate, but Beijing’s dependence on the city runs far deeper than it might appear.

Source: The Wall Street Journal, Nathaniel Taplin, September 10, 2019