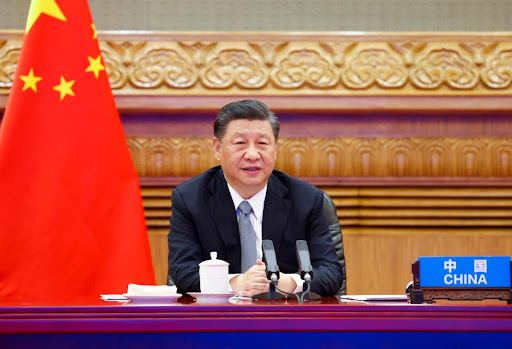

Xi Jinping stunned the world over the weekend. The Chinese leader’s Oct. 9 speech left no doubt about his commitment to the ultimate incorporation of Taiwan into the People’s Republic of China. But it was what President Xi didn’t say, and the context in which he didn’t say it, that mattered most.

Tension over Taiwan has been mounting for months. In a major speech commemorating the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, delivered in Tiananmen Square in July, Mr. Xi promised to “utterly defeat” any attempt toward Taiwanese independence. In a letter congratulating Eric Chu on his election as leader of Taiwan’s main opposition party, Mr. Xi called the situation on the island “complex and grim.” Over the weekend of China’s Oct. 1 National Day, a record 149 Beijing military aircraft crossed into the island’s air-defense identification zone.

The reasons for Beijing’s ire aren’t hard to find. Weeks after Australia helped form the Aukus partnership, former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott paid a visit to Taiwan. A French senator visiting the island called Taiwan a country. Japan’s incoming prime minister announced that longtime pro-Taiwan politician Nobuo Kishi will keep the defense portfolio in the new government. This month, a large Taiwanese delegation is scheduled to visit Eastern and Central Europe, where Lithuania has drawn Beijing’s ire by allowing Taiwan to open a diplomatic office. A recent six-nation joint naval exercise in the Philippine Sea was intended to signal growing allied resolve.

More striking still, last week this newspaper broke the news that U.S. Marines and special forces have been rotating through training missions on the island for more than a year. Beijing hawks, speaking through the Global Times newspaper, have called the presence of U.S. troops on Taiwan “a red-line that cannot be crossed” and warned that in the event of war in the Taiwan Straits, “those U.S. military personnel will be the first to be eliminated.”

Given all this, the relative restraint in Mr. Xi’s latest speech was remarkable. It was a speech Deng Xiaoping could have given, referring to peaceful reunification on the “one country, two systems” basis with no explicit military threats. And after White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan’s latest talks with Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi, Presidents Biden and Xi are still on for a virtual summit sometime this fall.

The answer has everything to do with politics at home. China is facing disruptive conditions. As the giant property developer Evergrande stumbles toward collapse, crackdowns on tech and other businesses have wiped out more than $1 trillion in asset values and made businesses jittery about the Communist Party’s next moves. At the same time a massive energy crisis has imposed widespread blackouts across much of China, while the more transmissible Delta variant presents the Chinese method of pandemic control with its harshest test yet.

The Chinese Communist Party is supposed to be bringing China to a new age of ease and plenty. That is not how things look to a middle-class family who invested their savings in Evergrande investment products, and who must walk up the stairs to their overpriced 10th-floor apartment because the power is out.

To keep the economy running, China must stroke its neighbors rather than slap them. It is all very well to threaten and insult Australia, but when your power stations across the Chinese Rust Belt have run out of fuel, you need Australian coal to keep the lights on. From Beijing’s point of view, this would be a terrible time for a major Taiwan crisis.

But the party also needs to keep nationalist opinion stoked at home. Communist China is supposed to be a rising superpower that others fear and respect. Beijing can’t afford to look as if it’s tamely accepting foreign encroachments on Taiwan.

And so Mr. Xi seems to have decided, for now, on a two-track foreign policy. The showy intrusions into Taiwan’s air-defense identification zone and the tough talk in Mr. Xi’s July speech painted a picture of a strong leader standing against the world. But the goal is to rattle sabers without starting a fight, while Beijing waits for better times.

This is a pause, not a change of direction. There are no signs that Beijing is reconsidering the basic assumptions of the Xi Jinping era that China is rising while America sinks. Before any serious rethinking of Beijing’s current policies of repression at home and aggressive competition abroad, China’s leaders would need to see evidence that the U.S. is more resilient than thought and that the Chinese domestic economic model is less robust than believed.

Source: Wall Street Journal |October 12, 2021 | By Walter Russell Mead