Why Trump’s America is rethinking engagement with China

The more aggressive US approach is part of a strategic shift that goes well beyond the trade war

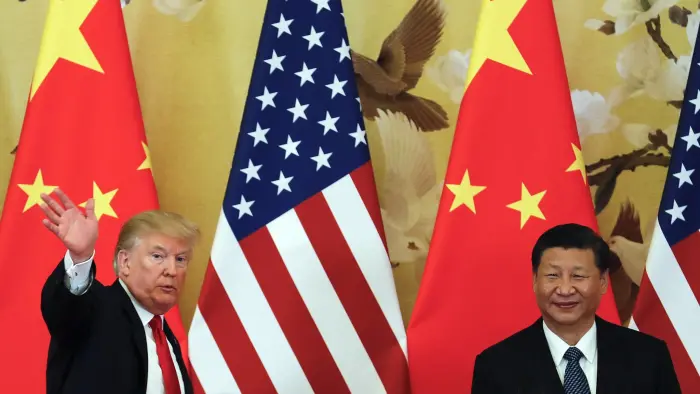

When Donald Trump sat down to dinner with Xi Jinping last month at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires, the US president did not know about the diplomatic bomb that was about to explode. At about the same time, police in Canada arrested a Chinese telecoms executive after an extradition request from Washington.

The detention of Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer of Huawei, was extraordinary because the US justice department had not told the White House about the warrant to arrest the daughter of the founder of the telecoms group, one of China’s most successful and influential companies.

But the importance of the arrest went well beyond the immediate circumstances. It is the most striking symbol yet of the dramatic deterioration in relations between China and a US that is increasingly suspicious of Beijing’s motives and actions. Reinforcing the rupture, the US several weeks later charged two Chinese nationals with conducting a global hacking campaign to assist the Chinese intelligence services.

While the trade war has received the most attention, the economic tussle is part of a much more profound shift in the US that has seen Washington reverse important elements of the strategy of engaging with its Asian rival that was first introduced more than 40 years ago by Richard Nixon.

Support for this change in approach has a broad base in the US. Officials across the US government have become significantly more hawkish towards China— over everything from human rights, politics and business to national security. At the same time, US companies and academics who once acted as a buffer against the harshest views are now far less sanguine.

“China has for some time underestimated the extent to which the mood in the US has shifted,” says Hank Paulson, the former US Treasury secretary. “The attitude that they would implement reforms at a timetable that made sense to them missed the fact that this was no longer sustainable if they wanted the US to keep its markets open to them. And the US business community now supports a harder line.”

While Mr. Trump likes to describe China’s president Mr. Xi as his friend, his White House signaled a major shift away from China when it labelled the nation a “revisionist power” in its December 2017 National Security Strategy. In October, Mike Pence, vice-president, hammered home that message in a speech at the Hudson Institute that charged China with a litany of offences — from political repression at home to coercive diplomacy abroad.

The rhetoric has been matched with action. In the South China Sea, the US navy is now conducting frequent freedom of navigation operations to push back against Chinese sovereignty claims over disputed reefs and islands. Meanwhile, the justice department created a “China initiative” task force to crack down on espionage.

While Ms. Meng was arrested for allegedly helping her telecoms company violate US sanctions on Iran, US officials have long worried that Huawei could help China spy on rivals. Those concerns escalated last year, culminating in the US convincing its Five Eyes intelligence-sharing partners — Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Britain — that they needed to take a much tougher line on Huawei, according to one person familiar with the situation.

While concerns about China have risen in parallel with its emergence as a rival to the US, Washington has concluded that it has underestimated the speed at which it has caught up with the US in terms of technology — particularly technology with military applications.

Dennis Wilder, former head of China analysis at the CIA, says that as the US war on terror has receded in urgency, intelligence and national security officials have now woken up to the fact that China was using a “whole-of-society” approach to collecting intelligence, and that the openness of the west to Chinese scientists, students and business people had become an “Achilles heel”.

“The Chinese intelligence operations were astoundingly successful in providing the military and other state-owned enterprises with the secrets to enable technological leaps that could only be possible with the theft of advanced critical technology from the US, Japan and Europe,” Mr. Wilder says.

Mr. Trump and his trade war have done a lot to change the mood but many experts say China would have faced a harsher climate regardless of whether he had won the 2016 election. One of the few areas where Democrats and Republicans are united is over the need to adopt a tougher stance towards Beijing.

Lindsey Ford, a former Pentagon official under Barack Obama, says US military officials started to become much more concerned about China in the second half of his administration, when it appeared that Mr. Xi was abandoning the “hide and bide” low-profile approach espoused by former leader Deng Xiaoping.

This was most striking in the rapid land reclamation in the South China Sea, where it installed weapons systems on some islands despite Mr. Xi having pledged to Mr. Obama in 2015 that China had “no intention to militarize” them.

Ms. Ford says the South China Sea activity was “the clearest signal that the game seemed to have shifted and that China’s own calculations about how much risk it was willing to accept . . . was no longer the same”.

At the same time that its navy has become more assertive, China has developed weapons-related technologies at a much faster pace than many US analysts once thought likely.

Underscoring how the gap between the US and China has shrunk, General Paul Selva, vice-chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, warned in June that “if we sit back and don’t react, we will lose our technological superiority in 2020”. The Pentagon is also concerned about the vulnerability of its military supply chains because of components made in China.

Washington is raising red flags about activities aimed at stealing US technology — whether via Chinese nationals working in American university labs or cyber espionage. One person familiar with the situation says US officials realized how much more vigilant they needed to become when they discovered just how much similarity there was between the Chinese J-20 stealth fighter jet and the American F-35.

To tackle the threat, the US has significantly stepped up the vetting of Chinese nationals who apply to study sensitive subjects in America. Christopher Wray, FBI director, last year warned Congress that US universities were naive about the potential for Chinese nationals to collect intelligence on their campuses.

John Demers, head of the justice department’s China Initiative, recently told the Senate judiciary committee that 90 per cent of economic espionage cases over the past seven years involved China. When the US charged the hackers in December, it said Beijing had breached a 2015 deal that neither nation would steal intellectual property for commercial advantages.

The US is also concerned about China trying to recruit American spies. In his testimony, Mr. Demers said the justice department had an “unprecedented” three cases against former US intelligence officers accused of spying for China. In May, the US charged a former CIA operative named Jerry Lee with illegally possessing secret information.

The CIA believes he provided Beijing with details about its spying operation in China. One person familiar with the situation says his actions dealt a catastrophic blow to the CIA’s network — as many spies were arrested or executed.

The US also believes that two suspected Chinese cyber attacks in recent years — one on the Office of Personnel Management which maintains government employee records, and another on the Marriott hotel group — were part of an operation designed to help China identify covert US intelligence operatives in the country.

As the US strikes a tougher tone, China is losing constituencies that once helped balance the more hawkish views in security circles. US academics who were seen as friendly to China are becoming warier as Beijing cracks down on human rights, not least those of the Uighurs held in mass detention centers in Xinjiang, fails to follow through on economic pledges, presses US scholars to be less critical and moves backwards in terms of political reform.

“People I’ve known for decades have given up on China,” says Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st century China Center at the University of California San Diego. “There’s a widespread view in the academic community that the overreaching China has done both domestically and internationally is hard-baked into the system and that there’s no hope of getting them to adjust their behavior to our interests and values.”

A turning point that alarmed Washington came in late 2017 when Mr. Xi did not name a successor at the Communist party’s 19th congress. He also pledged that China would become a fully modern economy by 2035 — picking a date that some saw as another sign that he intended to remain in power following his second five-year term. In a further sign of centralizing power, the National People’s Congress approved last March a change in the constitution to remove the two-term limit on the presidency.

A turning point that alarmed Washington came in late 2017 when Mr. Xi did not name a successor at the Communist party’s 19th congress. He also pledged that China would become a fully modern economy by 2035 — picking a date that some saw as another sign that he intended to remain in power following his second five-year term. In a further sign of centralizing power, the National People’s Congress approved last March a change in the constitution to remove the two-term limit on the presidency.

More recently, Mr. Xi reignited concerns that he was moving backwards on promised reforms when he used a speech commemorating China’s economic opening 40 years ago to stress the primacy of the party. “No one is in a position to dictate to the Chinese people what should or should not be done,” he said in December.

One senior US administration official says China has misread the change of mood in the US, adding that “even more disturbingly, they just don’t care”. The official says the fact that Mr. Xi’s speech had focused on “the growing role of the Communist party in every aspect of economic, political and personal life in China” suggested that Beijing was not taking the US concerns seriously.

“I don’t see signs of a course shift by the top leadership,” says the official.

“I never thought China would aspire to be a Jeffersonian democracy or espouse the western liberal order,” says Mr. Paulson. “I always thought the Communist party would be paramount, but I didn’t see the clock being turned back.”

Ms. Shirk says a major reason for the growing US backlash is that the business community has “really soured on China”. “Right now, it is totally out of balance because the national security concerns are completely dominating the process and the business community isn’t resisting,” she says.

Ryan Hass, a former White House official now at the Brookings Institution, says many US companies had “promise fatigue”. While many did not agree with the approach Mr. Trump was taking on trade, they wanted him to be tough on China on market access and were “trying to use Trump’s instincts for disruption

“The Chinese leadership has promised for years that reform was around the bend and then you see things like President Xi’s speech where he emphasized the central role of the party,” says Mr. Hass. “Members of the business community see the Trump administration as an opportunity for the US to rattle the cage in Beijing.”

Susan Thornton, the top Asia official at the state department until last summer, says many of the grievances had existed for years but Mr. Trump was giving them impetus because there was no one inside his administration who was weighing those concerns against the broader China relationship.

“There is no one imposing discipline right now. Everybody has now got a hunting license. It is open season on China,” says Ms. Thornton. One reason the Chinese may have been blindsided by the changing US approach is that Mr. Trump rarely raises security issues. “Trump never brings up any of that stuff in meetings with the Chinese,” she says. “He won’t bring up Taiwan or the South China Sea, or nuclear missiles or arms control, or espionage.”

Just before New Year, Mr. Trump tweeted that he had spoken to his Chinese counterpart and that there had been “big progress” on trade. But the landscape has changed so dramatically that most China experts believe the relationship will become much more rocky even if there is an agreement on trade.

“I am cautiously optimistic that President Trump will be able to declare a trade victory and end the tariff war,” says Mr. Paulson. “But there will still be so many intractable economic and security issues that this will continue to be a very fraught relationship.”

Source: Financial Times, January 16, 2019 | Demetri Sevastopulo