China ended the Year of Covid in many ways stronger than it started, accelerating its movement toward the center of a global economy long dominated by the U.S.

While the U.S. and Europe wait for vaccine rollouts to get fully back on track, China is the only major economy expected to report growth for 2020, helping it close the gap with the U.S.

It has expanded its role in global trade and shored up its position as the world’s factory floor, despite years of U.S. efforts to persuade companies to invest elsewhere. China’s consumer market—lifted by its quick recovery from Covid-19—keeps gaining momentum, making it a bigger driver of global companies’ earnings.

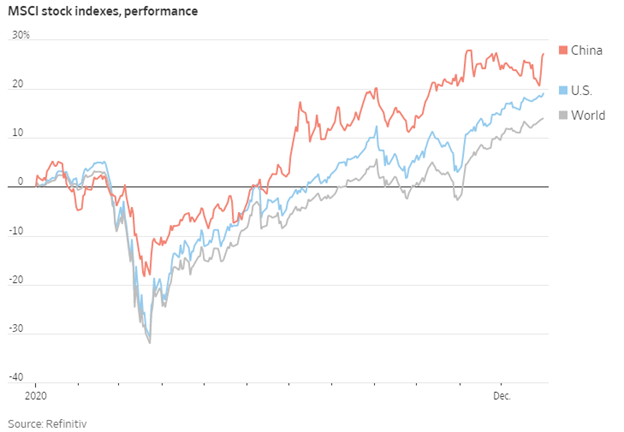

And the country has solidified its standing as a force in global financial markets, with a record share of initial public offerings and secondary listings in 2020, large capital inflows into stocks and bonds, and indexes that far outperformed even the U.S.’s strong showing.

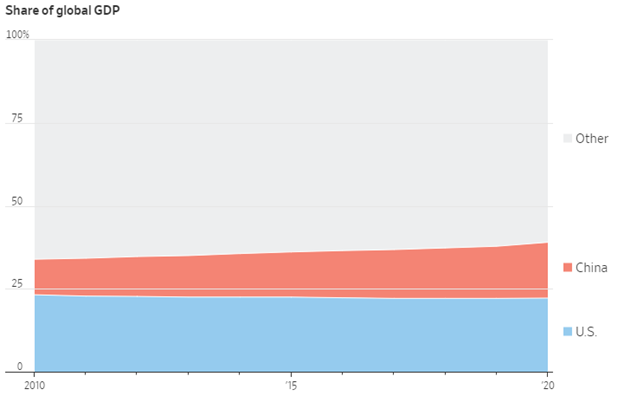

The upshot is a world more reliant on China for growth than ever before. For 2020, China’s economy is expected to account for 16.8% of global gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation, according to forecasts by Moody’s Analytics. That’s up from 14.2% in 2016, before the U.S. and China entered a trade war. The U.S. is expected to make up 22.2%, virtually unchanged from 22.3% in 2016.

China’s 2020 increase in its share of global GDP—1.1 percentage points—is its largest in a single year since at least the 1970s.

Share of global GDP Source: Moody’s Analytics Note: Figures are calculated based on real GDP in U.S. dollar terms. 2020 figures are estimates

The country is scheduled to report fourth-quarter and annual growth on Jan. 18, a moment that’s likely to confirm its ascendancy.

The gains are a testament to China’s success in containing Covid-19 and getting its businesses humming again. The country’s stimulus programs, which were smaller as a portion of the overall economy than in the U.S., focused on restoring factory production and keeping small businesses from going bust, with relatively little direct support for consumers.

That strategy paid off when, unusually in a recession, U.S. consumers kept spending heavily. Chinese factories were ready to serve them. That helped support Chinese jobs and China’s own consumer spending through the rest of the year.

Packages are sorted at a JD.com Inc. delivery hub in Beijing in November.

PHOTO: SIMON SONG/SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST/ZUMA PRESS

China also benefited because it is hard for foreign manufacturing firms to relocate, even after pandemic disruptions left many executives wanting to diversify their supply chains. Companies have to weigh losing the network effect of having so many other suppliers nearby, as well as the risks of moving elsewhere after China has proved so reliable.

A November survey by HSBC Holdings PLC of more than 1,100 global corporations found that 75%, including 70% of U.S. companies, expect to increase their supply-chain footprint in China over the next two years.

Trade tensions

For the rest of the world, China’s success is a double-edged sword. Chinese demand has been a godsend for businesses that sell to China, including commodity producers as well as auto makers and luxury-goods companies that lost sales elsewhere.

China’s renewed strength has also left businesses more exposed to a country whose leaders have made clear they want to reduce China’s reliance on foreign companies in favor of building up more of its own corporations.

In Australia, nearly 42% of the country’s goods exports went to mainland China in October, near the all-time monthly high from earlier in the year, before slipping to 37% in November, according to Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

While Chinese buying of Australian iron ore has helped cushion the Pacific nation’s economy, which experienced its first recession in 29 years, it has also added uneasiness—especially when China imposed restrictions on imports of Australian beef, barley and wine after Canberra pushed for more scrutiny of Covid-19’s origins.

While Chinese buying of Australian iron ore has helped cushion the Pacific nation’s economy, which experienced its first recession in 29 years, it has also added uneasiness—especially when China imposed restrictions on imports of Australian beef, barley and wine after Canberra pushed for more scrutiny of Covid-19’s origins.

“Have we become too reliant on China? The answer is clearly yes,” said Saul Eslake, a former chief economist at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd.

In the U.S., the Trump administration’s tariffs on China were meant to address imbalances in the global economy and level the playing field between the two countries.

Instead, China is expected for 2020 to record the biggest surplus in its current account—the broadest measure of a country’s transactions with the rest of the world—in history for any country, according to Capital Economics, a research firm.

Still, measured as a percentage of world GDP, China’s account surplus was even bigger in 2007 and 2008.

China continues to face some big economic challenges, including an aging population and rising labor costs, which make manufacturing more expensive. A recent rash of credit defaults by state-owned enterprises has added to longstanding worries over debt. And its momentum in manufacturing could ebb this year, if other parts of the global economy begin firing on all cylinders again.

Some economists say the country’s state-led economic model has blunted private-sector innovation that is potentially vital to China’s future.

Since Covid-19 emerged, however, China’s economy has been resilient, bolstering Beijing leaders’ belief that their system offers a more dependable alternative to Western democratic capitalism, especially during times of crisis.

The U.S. remains the world’s No. 1 economy, with the largest consumer market, a much higher standard of living and a currency whose importance dwarfs that of the Chinese yuan. America’s GDP is 50% greater than China’s.

The U.S. is also grappling with extreme political stress. This year, it is expected to grow around 3%-4%, but its economy likely won’t get back to its 2019 size until the second half of the year, according to some economists’ forecasts.

China is expected to grow as much as 9% this year, according to Morgan Stanley estimates.

“China will always remain our main market,” said Chung Yong-soo, director of the global business management division at South Korean snack maker Orion Corp. , best known for a marshmallow-filled treat called “Choco Pie.”

The company launched a tie-up with PepsiCo Inc. in the 1980s to bring new products it could sell in the South Korean market. Increasingly, though, selling its products in China is what matters most to its bottom line.

Orion’s operating profits in China jumped 28% in the first three quarters of last year compared with the same period a year earlier, thanks to the introduction of new products into the market, including glutinous rice cake-inspired Choco Pies. China sales accounted for 48.2% of Orion’s overall revenue in 2019, compared with 38.7% in 2010.

Factories restarted

For years, economists warned that China’s rising labor costs, deepening debt and ebbing productivity gains would imperil its status as the world’s factory floor. The trade war and higher tariffs further cut into China’s advantages.

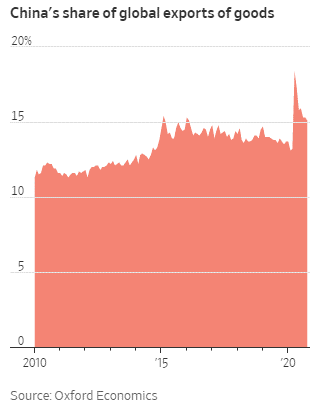

But China’s share in global exports of goods is still growing. It was 15.4% in November, the most recent month for which data was available, compared with 13.7% late 2019, before the pandemic came into full swing, according to Oxford Economics.

The gain was driven in part by China’s quick pivot to sell personal protective equipment, such as masks and respirators, whose sales have surged during the pandemic.

Beijing forcefully intervened to contain Covid-19 and help keep factories and businesses open. It sealed off large parts of the country and barred people from leaving their homes for extended periods, moves that would be difficult in countries with more freedoms.

About 4,600 people have died in China as a result of the pandemic, according to the country’s health ministry, although that number is thought to be underreported by some researchers. In the U.S., the death toll is close to 380,000.

It ordered state-owned banks to halt debt collection on affected businesses and individuals while offering fresh credit to small firms at cheaper-than-usual rates. Local officials required factory owners to meet tough standards to ensure safe operations, including, in some cases, tracking workers’ connections to affected regions.

Welders work on auto parts in Weifang in June.

PHOTO: AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

Many local governments, including the city of Foshan, dispatched shuttle buses to bring migrant workers stranded in villages back to factories once the virus was gone. Larger manufacturers, such as Foxconn Technology Group, which assembles Apple Inc. products in China, offered workers bonuses up to $430 per person to come back to work.

Chen Xin, co-founder and general manager of Foshan Nuobio Electrical Appliance Co., said he personally worked on his company’s assembly line along with two partners and their wives to ensure orders for air purifiers were met during the pandemic. Local authorities made sure the factory passed inspections before reopening, the 37-year-old Mr. Chen said.

By mid-March, nearly all of Nuobio’s roughly 50 suppliers had resumed production, he said. All are located within 50 kilometers of the factory. “That’s the biggest advantage that China offers. Nowhere else can you find such a comprehensive and close-knit supply-chain network,” Mr. Chen said.

With consumers in the West spending more time at home, orders from overseas surged, and Nuobio benefited. The company’s sales rose about 20% in 2020.

By early April, more than 97% of China’s larger enterprises had reopened, according to Zhang Weihua, an official with China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Other companies, including consumer electronics manufacturers, saw stronger-than-usual export orders. In November, China’s exports grew at their fastest pace in nearly three years, resulting in a record trade surplus of $75 billion that month. It dipped a bit in December.

Some buyers of Chinese goods weren’t eager to resume sourcing there, worried they had become too dependent. But they found other alternatives weren’t as good.

In Australia, Conga Foods recently launched a line of locally made vinegars to reduce imports from Europe and tap into growing consumer demand for domestically made products. The company needs glass bottles for the vinegar from China because no suitable bottles are made in Australia, said David Valmorbida, director at the company.

“If we would have a reliable production source in Australia of the required bottles that are priced competitively, then we would definitely prefer to buy that locally,” Mr. Valmorbida said.

Kleva Health, a San Francisco-based startup that sells at-home Covid-19 testing kits, needed large numbers of saliva collection tubes last summer.

David Yu, the company’s 31-year-old founder, said he initially decided to go with tubes made in Canada but abandoned the plan after finding that ones made in southeastern China were less expensive and more accurate.

The company is awaiting approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to sell the testing products to average Americans.

Expanding consumer market

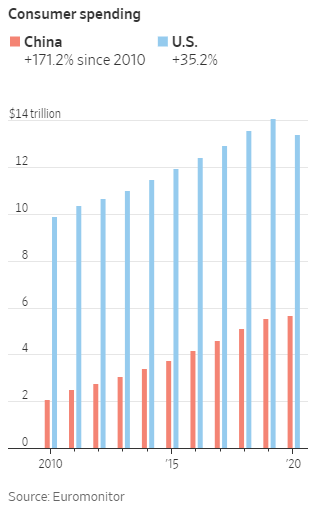

Consumer spending in China bounced back by the fall. China’s personal luxury-goods market is expected to have grown 7.6% in 2020, even as the global market cont

racted 20%, according to research firm Euromonitor International.

“While the rest of the world has stopped spending, the Chinese have carried on,” said Fflur Roberts, Euromonitor’s head of luxury-goods research.

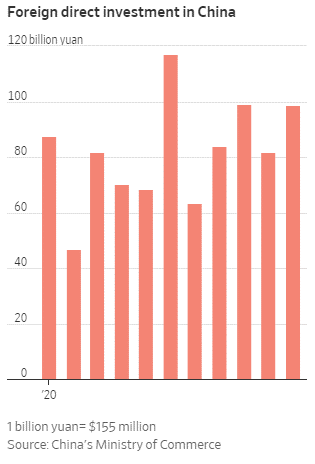

While foreign direct investment, such as by businesses for production assets abroad, into the U.S. and Europe plummeted in the first half of this year, it largely held steady in China, where it was up 6.3% through November, compared with the previous year’s 11 months, according to China’s commerce ministry.

Money has flowed into China in other ways, adding momentum to its long-term goal of building up important domestic financial centers. Chinese markets, including in Hong Kong, accounted for 43% of the world’s public listings last year, according to data from Refinitiv.

Foreign holdings of Chinese bonds hit a record 3.25 trillion yuan, or about $503 billion, in December, up 49% in a year, according to data compiled by Bond Connect Co.

The MSCI China index, which includes Chinese companies listed at home as well as those that trade in New York or other locations, rose 27% in dollar terms last year. The MSCI AC World index is up 14% in the same period, and MSCI’s U.S. benchmark added 19%.

Source: The Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2021 | Stella Yifan Xie, Eun-Young Jeong and Mike Cherney